The quest for highly specific, stable, and low-cost chemical sensing has found a powerful answer in molecularly imprinted polymers. These synthetic materials, often called "plastic antibodies," are engineered to have tailor-made cavities that selectively recognize and bind target molecules with an affinity rivaling biological systems. For smart mask technology, the latest MIP sensors offer a breakthrough: the ability to detect specific pathogens, toxins, or biomarkers directly from breath or the air, with the ruggedness and shelf-life of plastic rather than the fragility of enzymes or antibodies.

The latest molecularly imprinted polymer sensors integrate advanced polymerization techniques and novel transducer mechanisms to create highly selective, robust, and miniaturized detectors for gaseous or particulate targets, enabling masks to act as real-time diagnostic or environmental monitoring platforms by converting the binding of a specific molecule into a measurable electrical, optical, or mass-sensitive signal. This technology moves beyond generic particle counters to identification-level detection, answering the critical question: "What specific threat am I exposed to?"

The market for biosensors is projected to exceed $36 billion by 2028, with MIPs gaining significant traction as stable alternatives to biological receptors. For a mask, an MIP sensor could continuously monitor for a specific industrial toxin, a signature volatile organic compound (VOC) of a disease, or even SARS-CoV-2 virions. The latest advancements focus on improving sensitivity, achieving faster response in dynamic airflows, and integrating seamlessly into wearable formats. Let's explore the state of the art.

What Novel Polymerization and Imprinting Techniques Enhance Selectivity?

The core of an MIP's performance lies in the fidelity of the molecular "imprint." Recent techniques have dramatically improved the match between the polymer cavity and the target molecule, even in complex matrices like humid breath.

How Does Surface Imprinting on Nanostructures Improve Performance?

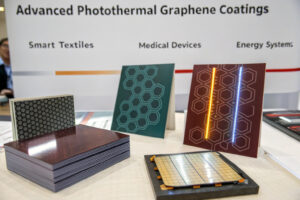

Surface-imprinted polymers (SIPs) represent a major leap. Instead of creating imprints buried within a bulk polymer block, the template molecules are immobilized on the surface of a nanoparticle (e.g., SiO₂, Fe₃O₄) or a nanowire before a thin polymer shell is grown around them. After template removal, the binding sites are highly accessible on the surface, drastically reducing the time for target molecules to diffuse in and bind. This is critical for the fast flow rates in a breathing mask. Furthermore, the nanoparticles can be functionalized with conductive materials (like graphene) or fluorophores to act as the transducer themselves. Sourcing these materials involves specialized nanomaterial and polymer chemistry suppliers.

What is the Advantage of Electropolymerization for Wearable Sensors?

Electropolymerization allows for the one-step synthesis of an MIP film directly onto the sensor's electrode surface. By immersing the electrode in a solution containing the target (template) molecule and monomers, and applying a specific voltage, a highly uniform, adherent, and thin (nanometer to micrometer) polymer film grows. This method offers exquisite control over film thickness and morphology, and the resulting MIP films often exhibit excellent rebinding kinetics and electrochemical activity. For mask-integrated electrochemical sensors, this is the preferred fabrication method. It requires sourcing monomers (like pyrrole, aniline, o-phenylenediamine) and access to cleanroom or controlled electrochemical setup for production.

What Transduction Mechanisms Convert Binding into a Signal?

The "imprint" provides selectivity, but a transducer is needed to convert the binding event into a readable electronic signal. The latest MIP sensors employ diverse and highly sensitive transduction methods.

Why Are Electrochemical MIP Sensors Leading for Wearable Integration?

Electrochemical MIP sensors are the frontrunners for mask integration due to their potential for miniaturization, low power consumption, and direct electronic readout. The most common configurations are:

- Capacitive/Impedimetric: Binding of the target within the MIP film changes its dielectric properties or charge transfer resistance, altering capacitance or impedance.

- Potentiometric: Binding induces a change in membrane potential.

- Voltammetric: The target molecule itself is electroactive, and its oxidation/reduction current is measured after being concentrated by the MIP.

Recent advances use conductive nanostructures (carbon nanotubes, graphene) within the MIP to enhance signal-to-noise ratio. Suppliers are emerging who offer screen-printed electrode (SPE) arrays pre-coated with MIPs for specific targets (e.g., cortisol, glucose for sweat; adapting these for gaseous targets is the next step).

Can Optical MIP Sensors Offer Superior Sensitivity?

Optical MIP sensors, particularly those based on fluorescence or surface plasmon resonance (SPR), offer exceptional sensitivity, potentially down to single-molecule detection. In a fluorescence-based MIP, a fluorophore is incorporated into the polymer matrix. When the target binds, it quenches or enhances the fluorescence signal. For masks, the challenge is miniaturizing the light source and detector. Emerging solutions use LEDs and photodiodes on chip-scale systems. A more promising wearable approach is MIP-based colorimetric sensors—where binding causes a visible color change readable by a smartphone camera. Sourcing involves finding developers of such indicator dyes and MIP composites.

What Targets Are Most Relevant for Mask-Integrated MIP Sensors?

The choice of target dictates the MIP design and the potential impact of the mask. The most promising targets fall into three categories: pathogen markers, environmental toxins, and human health biomarkers.

How Can MIPs Detect Specific Pathogens Like Viruses?

Directly detecting an entire virus is challenging due to its size. The strategy is to detect unique surface proteins or glycans. For example, an MIP can be templated with a synthetic peptide mimicking a conserved region of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein's receptor-binding domain (RBD). When virions are present in exhaled breath condensate or captured aerosols, the spike proteins bind to these cavities. This can be coupled with an electrochemical transducer for detection. Research in Biosensors and Bioelectronics has demonstrated prototype MIP sensors for influenza and coronavirus. Sourcing this technology is at the advanced research prototype stage, often through university partnerships.

What Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) Serve as Effective Targets?

MIPs are excellent for smaller, volatile molecules. Key targets include:

- Toxins: Formaldehyde, benzene, toluene from industrial or indoor air.

- Disease Biomarkers: Acetone (for ketoacidosis/diabetes), ammonia (for kidney dysfunction), alkanes (for oxidative stress), and nitric oxide (for asthma inflammation) in exhaled breath.

MIPs for these VOCs are more mature. For instance, formaldehyde-selective MIPs using phloroglucinol as a monomer are well-documented. The challenge for breath analysis is the humid and complex matrix, which requires MIPs with exceptional selectivity to ignore the vast background of water and other endogenous VOCs.

What Are the Integration and Operational Challenges for Masks?

Moving from a lab sensor to a functional component in a breathing mask involves solving problems of sampling, regeneration, and environmental robustness.

How is Air Sampled and Delivered to the Sensor?

A mask cannot pass the entire airflow over a small sensor. An integrated system requires a micro-sampling system. This could be a passive, bifurcated channel that diverts a small, proportional fraction of the breath stream to a micro-chamber containing the MIP sensor. Alternatively, a micro-pump could be used for active sampling, but this consumes power. The design must ensure rapid equilibration between the sampled air and the sensor to provide real-time readings without significant lag.

Can MIP Sensors Be Regenerated for Reuse?

A major advantage of MIPs over antibodies is potential regeneration. After detection, the bound target molecules can often be removed by washing with a specific solvent (e.g., a mild acid or organic mixture) or by applying a voltage pulse (for electrochemical sensors), resetting the sensor. For a reusable mask, this could mean the sensor is regenerated during a nightly cleaning cycle. However, regeneration protocols must be proven over dozens or hundreds of cycles without loss of sensitivity. Not all MIP-target pairs allow for gentle regeneration. This is a key specification to demand from a supplier.

Conclusion

The latest molecularly imprinted polymer sensors represent a convergence of materials science, nanotechnology, and transducer engineering, bringing laboratory-grade chemical specificity to the brink of wearable integration. For mask technology, they offer a path beyond counting particles to identifying threats—be it a specific virus, a dangerous toxin, or a tell-tale biomarker of illness. While challenges in sampling, miniaturization, and long-term stability in humid environments remain, the pace of advancement is rapid. The most immediate opportunities lie in environmental toxin monitoring, with pathogen and biomarker detection following as the technology matures.

Ready to explore integrating specific chemical intelligence into your smart masks with MIP sensors? Contact our Business Director, Elaine, at elaine@fumaoclothing.com. We are tracking developments in advanced sensor materials and can help you connect with pioneering developers to prototype and test this transformative technology for your applications.