The frontier of personal protective equipment is being redefined by the advent of programmable matter—materials and components whose physical properties can be digitally controlled and reconfigured in real-time. This represents a paradigm shift from static, one-size-fits-all masks to dynamic systems that actively adapt their form, function, and filtration characteristics to the individual user and changing environment. For innovators in smart textiles, wearable tech, and advanced manufacturing, understanding these emerging components is key to building the next generation of responsive, personalized protective gear.

Programmable matter mask components are structures or materials composed of modular or smart material units that can change their shape, stiffness, optical properties, porosity, or other physical attributes in a controlled, reversible manner in response to digital commands, enabling masks that self-adjust their fit, optimize filtration on-demand, and integrate adaptive features like dynamic messaging or thermal regulation. This technology moves beyond simple shape memory to encompass systems that can be programmed with multiple stable states and transition between them based on complex logic. The most advanced implementations leverage principles from robotics, materials science, and information theory to create matter that is, in essence, software-defined.

The field of programmable matter is nascent but rapidly accelerating, with research from institutions like MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms demonstrating functional prototypes. Applications in adaptive PPE could revolutionize comfort, protection efficiency, and user compliance. Let's explore the most promising types of programmable matter components emerging for mask applications.

What Are Modular Robotic (Claytronic) Mask Frameworks?

Inspired by concepts like claytronics, this approach envisions a mask constructed from a multitude of tiny, programmable robots (or "catoms") that can move relative to one another, collectively forming any desired macroscopic shape.

How Would Catom-Based Systems Achieve Custom Fit?

Each catom would contain micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS) for locomotion (e.g., electrostatic or magnetic actuation), sensing, communication, and computation. Upon donning, the cloud of catoms would:

- Sense the Face: Using onboard proximity or pressure sensors to map facial topography.

- Compute Optimal Configuration: A distributed algorithm would determine the arrangement that forms a perfect seal with uniform pressure.

- Self-Assemble: The catoms would move into position and lock together (perhaps magnetically or via mechanical latches) to form a rigid, sealed structure.

This would guarantee a personalized fit for every user, eliminating the need for multiple sizes and dramatically improving protective efficacy. The mask could also reconfigure mid-use—for example, temporarily relaxing the seal around the mouth to facilitate drinking. Research in this area is heavily simulation-based currently, but advancements in milli- and micro-robotics are making hardware prototypes increasingly feasible.

What are the Formidable Challenges?

The challenges are immense: powering and controlling millions of tiny units, ensuring robustness and washability, and achieving practical manufacturing costs. Early-stage applications might use a semi-modular approach, where larger, reconfigurable segments (e.g., a programmable nose bridge and adjustable cheek panels) provide most of the fit adaptation benefits without the complexity of full granularity.

What Are Phase-Changing and Jamming Transition Materials?

These are bulk materials whose macroscopic mechanical properties (like stiffness) can be switched on demand, offering a simpler path to programmable fit and comfort compared to modular robotics.

How Do Granular Jamming Structures Work?

A granular jamming component consists of a flexible pouch filled with small particles (like coffee grounds, silica gel, or expanded glass beads). In its normal state, the pouch is soft and moldable.

- Programming Rigidity: When air is evacuated from the pouch (via a tiny integrated vacuum pump), atmospheric pressure compresses the particles together. Friction between the jammed particles causes the entire structure to become dramatically stiffer, locking into its current shape.

- Application: This could be used in a mask's seal. The user dons the mask, molds the soft jamming seal comfortably to their face, and then activates a button. The pump removes air, jamming the seal into a custom-molded, rigid gasket that maintains perfect contact. Releasing the vacuum returns it to soft for removal or re-adjustment.

This technology, explored by projects like MIT’s "jammable" wearables, is relatively low-tech and highly effective for creating customizable rigid structures from soft precursors.

Can Low-Melting-Point Alloys (LMPA) Be Used for Shape Programming?

Embedding channels or a mesh of a low-melting-point alloy (e.g., Field's metal) within a flexible mask structure offers another pathway. In its solid state, the alloy provides a rigid exoskeleton.

- Programming Softness: Applying a small electrical current (via integrated traces) resistively heats the alloy above its melting point (often 60-70°C), making it liquid and allowing the mask structure to become flexible for donning, doffing, or adjustment.

- Programming Rigidity: Cutting the current allows the alloy to solidify, locking the mask's shape.

This allows for repeated re-programming of a rigid form factor. The challenge is containing the liquid metal and managing heat to ensure user safety and comfort.

What Are Dynamic Surface and Optical Components?

Programmable matter isn't just about shape; it's also about surface properties. Components that can change their optical characteristics or topography open doors for adaptive functionality and communication.

How Do Electrochromic and Thermochromic Fabrics Work?

- Electrochromic Fabrics: Incorporate materials (like conductive polymers or tungsten oxide) that change color or opacity when a small voltage is applied. This could be used for programmable camouflage, switching between high-visibility colors for safety and low-visibility for discretion, or displaying simple status icons (battery level, filter status).

- Thermochromic Fabrics: Change color with temperature. While often passive, they could be actively programmed using integrated micro-heaters to display information or patterns. For example, a pattern could appear only when the user has a fever.

These technologies move the mask from a passive object to an interactive display surface, albeit with limited resolution and color range currently.

Can Surface Topography Be Programmed for Function?

Imagine a mask's exterior covered with microscopic scales or pillars, akin to a butterfly wing or shark skin.

- Passive Programming: By pre-structuring the material, these surfaces can be engineered to be superhydrophobic (shedding water and droplets) or to manipulate airflow to reduce drag.

- Active Programming: Using micro-actuators (like those in a Digital Micromirror Device), the angle or position of these micro-features could be tuned dynamically. This could allow the mask to switch between a smooth, low-drag surface for easy breathing and a textured, high-friction surface to disrupt and filter airborne particles more effectively upon command.

What Are the Integration and Control Challenges?

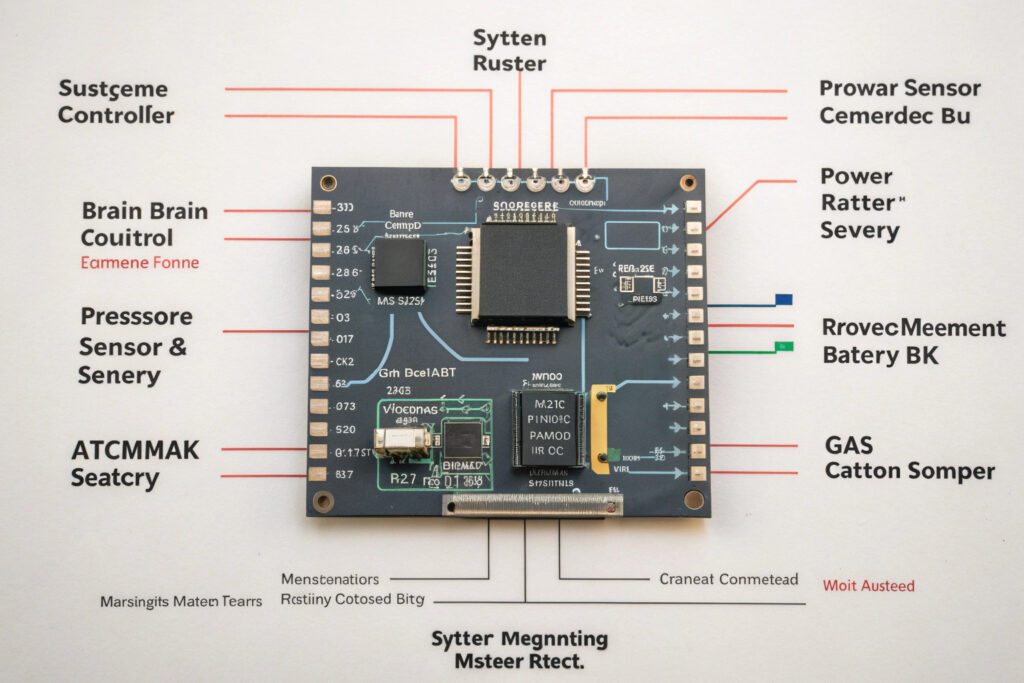

Harnessing programmable matter requires more than just the material; it demands a complete ecosystem of control, power, and sensing to be practical.

How is Distributed Control Managed?

For systems with many independent units (like catoms or an array of micro-actuators), centralized control is impractical. The solution is distributed or swarm intelligence.

- Each unit runs simple rules based on local sensor data and communication with immediate neighbors.

- Global behavior (like "form a seal") emerges from these local interactions, making the system robust and scalable.

This requires sophisticated algorithm development and efficient, low-power inter-unit communication protocols (like near-field capacitive coupling).

What Are the Power and Durability Hurdles?

Actuation—whether moving a catom, jamming granules, or melting an alloy—consumes energy. While holding a state (like being jammed) can be low-power, transitioning between states often is not.

- Energy Scavenging: Future systems may incorporate energy harvesting (e.g., from breathing motion or temperature differences) to supplement small batteries.

- Wear and Tear: Components that physically move or change phase are subject to fatigue and eventual failure. Cycle life (the number of reliable shape changes) is a critical metric. Manufacturing these components to withstand the moisture, temperature variations, and mechanical stresses of daily mask use is a primary engineering challenge.

Conclusion

Emerging programmable matter components—from modular robotic frameworks and jamming structures to dynamic surface pixels—promise a future where masks are not worn but assembled onto the face for a perfect fit, and where their functionality (filtration, communication, thermal management) can be updated and optimized through software. While many of these concepts are in early research or proof-of-concept stages, they chart a clear course for the evolution of PPE: away from static, passive objects and towards intelligent, adaptive, and highly personalized protective systems. The path to commercialization will involve simplifying these concepts into robust, manufacturable sub-components that deliver immediate, tangible benefits in fit, comfort, or user interaction.

Ready to explore how the principles of programmable matter can inspire the next leap in mask technology? Contact our Business Director, Elaine, at elaine@fumaoclothing.com to discuss conceptual development, prototyping, or sourcing strategies for integrating adaptive, smart material components into your advanced product roadmap.